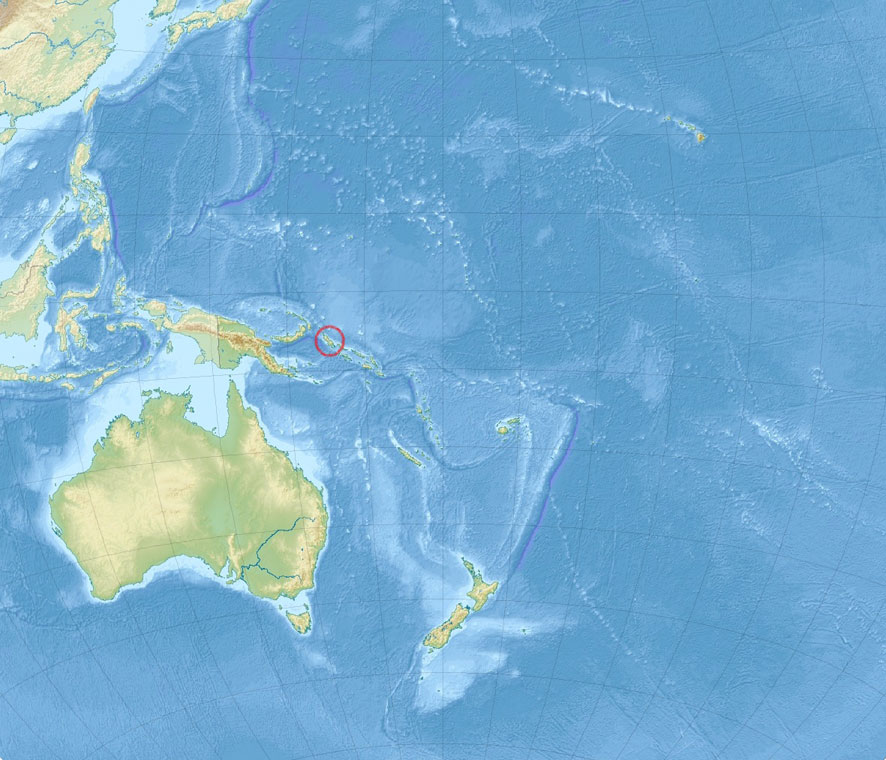

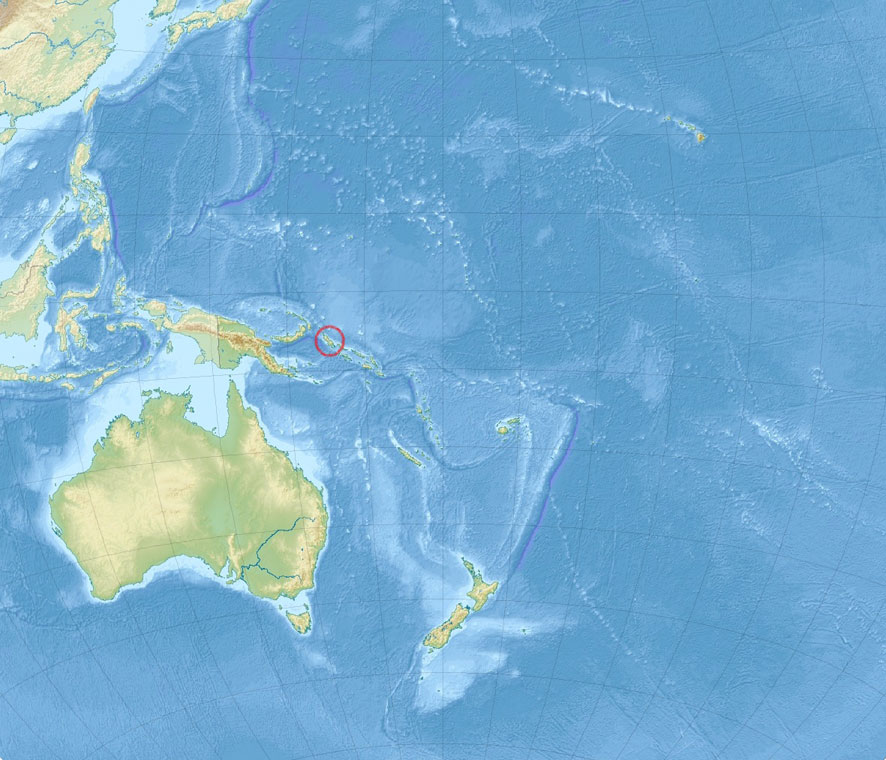

(October 27, 1943 – March 1944)

After New Georgia, the US launched their next major operation with the invasion of Bougainville, the largest island in the Solomon archipelago. Bougainville had been occupied by the Japanese since 1942. There and at nearby islands, the Japanese had constructed naval aircraft bases to support their main garrison at Rabaul on New Britain Island. Victory at Bougainville would be key for the Allied Forces in their overall objective of isolating Rabaul.