ORAL HISTORY CLIPS

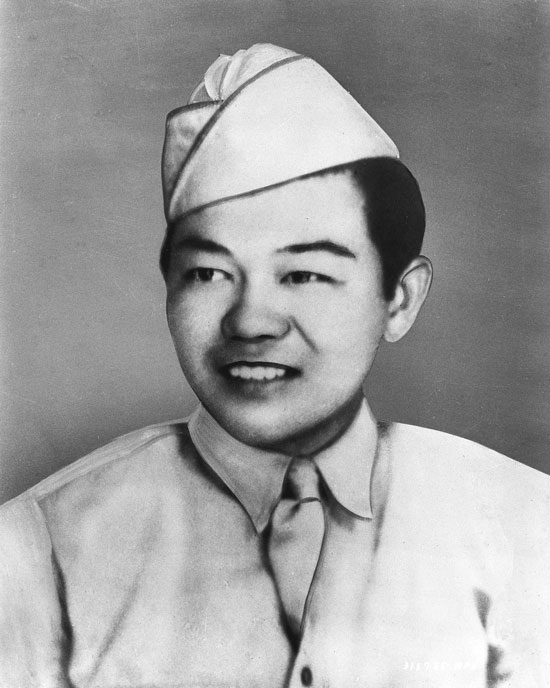

James Oura [interview 625]

Starts on Tape Four

JAMES OURA:

But you know, on this Lost Battalion —you see on the 27th . . . and this is the 22nd, October 27th . . . only a few more days . . . is just when we started to go out to rescue the Lost Battalion. And every October, this is my feeling, I will take out a manual, a book, a history of the 442nd and I’ll come down to the Lost Battalion. And I’ll read about it and sort of memories come back, you know, keep on coming back, but I shed a lot of tears . . . reading about it. But every October 27th I have this feeling that I have to read and think back of all the guys we lost. But I don’t know when I’ll get over the feeling, but 27th is close by and my books will be ready to be read again.

James Matsumoto [interview 300]

Starts on Tape Five, between 14 and 16 minute marks

JAMES MATSUMOTO:

We had a big, big, big battle there at Bruyères. We’d finally liberated that town, but there were so many dead people on the road that they had to bring a bulldozer to push ’em off the road. We lost a lot of men there. We took that town. We battled night and day. And then they finally got rest, but we liberated it, the Germans pulled back. And the line was broken, and that’s when they were—Lost Battalion started. 141st Battalion from the 36th Division got suckered into—the Germans opened up the area there that they were pushed into and opened it up, and then those guys went in there and then the Germans closed them up behind ’em. So we only had a day and a half rest. And they said “Okay, get ready, we got another push. We gotta go rescue this Lost Battalion. They said, “Rescue them at any cost.” So that was our big job.

Rudy Tokiwa [interview 183]

Starts on Tape Eight

RUDY TOKIWA:

And I’ll never forget that one of their units got surrounded. And they were about 10 miles in, and I was—they must have got sucked. And, you know, they had three times the men of us besides the ones that we’re in fighting already, because they were a big unit and we were just a small regiment. And—but, no, we were given the orders to go back in and make the rescue. I’ll tell you how long we were back on the rear echelon was, we got to the area we were supposed to rest for the night. So we got out of the trucks, we put our sleeping bags out, and before we know it we’re putting the sleeping bags and wrapping ’em back up and getting ready to move out. And I’ll tell you how dark it gets in the Vosges Forest. On the night when there’s no moon or anything, you walking in the Vosges Forest, if you put your fingers out like that, you won’t see your hand.

Starts on Tape Eight, between 14 and 16 minute marks

RUDY TOKIWA:

And I’ve always felt sorry because, when we were going after—going in to make the rescue of the 36th, there was a regimental battalion out of the 36th that got surrounded in the Vosges Forest, and, you know, the 36th has four times the amount of men we do, but we’re the ones that they want to go in and make the rescue. So we started going in to make the rescue. But we—like the company I was in, we had a little over 300 men when we started out. And we went in and it took us over six days to make the rescue. And I’ll show you how bad the battles were. When K Company came out, there was only 17 people left.